- Home

- Elin Hilderbrand

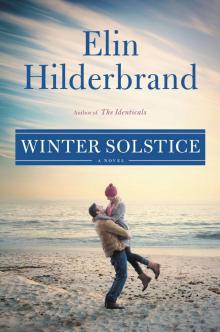

Winter Solstice Page 21

Winter Solstice Read online

Page 21

“A relief,” Glenn says. “Because I have a buyer for the Winter Street Inn.”

“It’s… it’s…” Allegra has clearly been eavesdropping, and now she’s snapping her fingers, looking at her father, trying to pull something out of the pocket of her brain where her schooling resides. “It’s that story, that Christmas story about the couple that have no money. She cuts her hair to make money to buy him a watch chain, and he sells his watch to buy her combs.”

“Exactly,” Eddie says. Maybe a year at UMass Dartmouth wasn’t such a waste after all. “‘The Gift of the Magi,’ by O. Henry.”

“It’s not really like that story at all,” Barbie says.

“It is a little bit,” Eddie says. “Because my story, the Christys’ story, is ironic. And, like the characters in the O. Henry story, the Christys were motivated by their love for each other and their desire to put the other person’s happiness first.”

“Sell the Christys the Wauwinet house,” Glenn says. “I’m putting the inn under agreement with my guy.” Glenn leans back in his chair. “This may not be as good a story as Eddie’s, it may not be O. Henry, but it’s still a story.”

“We’re all ears,” Eddie says.

“My buyer for the Winter Street Inn is this guy who used to stay there. He stayed there for twelve years at Christmastime. So obviously this guy—George Umbrau, his name is—knows Mitzi and Kelley, and he wants to surprise them by paying full price for the inn. In cash. I guess this guy used to make hats—there’s a fancy name for it, which I forget—and one of his hats showed up in Vogue magazine, and right away someone swooped in to buy up his hat business for eight figures. So he has the six and a half million. He says he’s in no hurry; he wants Mitzi and Kelley to stay at the inn as long as they’re able, and when they’re ready or Mitzi is ready to move on, then he’ll take over. And he says he’s committed to keeping the inn exactly as it was when the Quinns ran it.” Glenn puts his hands behind his head. “Now, is that guy Santa Claus, or what?”

“Santa Claus?” Eddie says, and a lightbulb goes on over his head.

AVA

Like everyone else in America in general and New York in particular, Ava spends the weeks before Christmas shopping. Only instead of shopping for presents, Ava is shopping for clothes to take to Austria!

“I feel so selfish,” she tells Margaret.

“Don’t,” Margaret says. “This is going to be a very special trip for you, I can feel it.”

How special? Ava wants to ask. Does Margaret know something Ava doesn’t?

Ava and Margaret are on the third floor of Bergdorf Goodman, in couture. Margaret is buying Ava a gown to wear to the New Year’s Eve ball at the palace. Initially, Ava told her mother that buying something new was unnecessary; Margaret has closets filled with gowns. Ava could simply go shopping in Margaret’s closets. But Margaret insisted that this ball was worthy of a new gown, one suited and tailored to Ava’s figure, coloring, and taste.

Ava tries on fourteen gowns before she finds the winner: a strapless ivory silk gown with a gold cord belt. It’s a goddess dress with a blouson bodice and a forgiving amount of room in the skirt. The ivory is flattering to Ava’s red hair and her complexion, and Margaret has a pair of long gold Mona Assemi earrings that Ava can borrow. They buy gold sandals with a modest heel—optimal for ballroom dancing—and a tiny gold clutch purse.

“Hair and makeup on me,” Margaret says. “You’re staying at the Grand Hotel Wien, right? I’ll call the concierge tomorrow to set it up.”

“But you’re already doing so much,” Ava says. “The dress, the shoes, the purse…”

“I’m lending you my fur shrug,” Margaret says. “Don’t let me forget to drop it off.”

“And my flight,” Ava says. Potter is leaving for Vienna on Tuesday, the nineteenth, because he has business to tend to before Ava arrives, he says.

“What kind of business?” Ava asked.

“I’m starting research on my Danube novel,” he said.

And before Ava could express her delight—at Columbia, like everywhere else, it’s publish or perish, and Potter had been talking about his Danube novel for months—he added, “And I’m arranging for some surprises for you.”

Ava will fly to Vienna by herself on Thursday, the twenty-first, and Margaret has insisted on upgrading Ava’s ticket to first class.

“You haven’t lived until you’ve flown first class on an international flight,” Margaret said. “Besides, I want you to arrive refreshed.”

Ava feels like something might be up, something big. Her mother’s insistence that this trip is special, something she will want to be fresh and ready for. Potter’s tease of surprises for Ava. But Ava won’t get her hopes up; she has been disappointed too many times in her life. Nathaniel “surprised” her three years earlier with a Christmas gift of Hunter boots with matching socks. And Scott “surprised” her by getting Mz. Oliveria pregnant.

Ava wants to believe in Potter. He did manage to fix the PJ issue—with help from Harrison. When Potter came home from California, he brought a drawing that PJ had done. The drawing showed five stick figures. PJ was in the middle, Trish and Harrison were to PJ’s right, and Potter and Ava were to PJ’s left. All of the figures were holding hands and the sun was shining above them.

The drawing was more than Ava could ever have hoped for. She made Potter tape it to his fridge.

“Just let me do things for you,” Margaret says as she gives the woman her Bergdorf card. She takes a deep breath. “You know how odd it is that it’s nearly six o’clock and I don’t have to be anywhere?”

“I bet it’s odd,” Ava says.

“Odd in the best possible way,” Margaret says. “Let’s go to the café and get a cocktail.”

Over the weekend Ava packs everything she’ll need for the trip. She has three days left of teaching, and then Thursday she flies. She can’t begin to explain how excited she is. Vienna and Salzburg at Christmas! The Mozart! The marzipan! Ava hopes that one of Potter’s surprises is a Sound of Music tour while they’re in Salzburg.

The hills are alive… !

Potter’s first surprise is that he swings by Copper Hill to kiss Ava good-bye before he heads off to JFK on Tuesday. It’s three o’clock and the school day is officially over, but Ava is in the conservatory with Justice DeMarco, who is working on an independent study project. Justice is composing his own ragtime piece on the piano, which is a noble pursuit, but Justice gets frustrated easily, and he feels that any direction in which he takes the chord progression sounds derivative.

“All ragtime sounds alike,” Ava tells him in an attempt to be reassuring.

“But I want to create a new ragtime,” Justice insists. “Ragtime a hundred years later.”

It’s at this point that Potter walks in. He watches Ava at work with Justice, and Ava can’t help but notice the awestruck look on his face. It’s the expression of a man in love watching his girlfriend work.

“Excuse me one second, Justice,” Ava says.

Justice goes back to banging out the chords while jangling out a melody with his right hand, and Ava pulls Potter behind the door to her office and gives him a juicy kiss.

“I’m really going to miss you,” he says.

“It’s only two days,” she says. She gives Potter another kiss, longer and very inappropriate for the workplace, then she shoos him out. “Have a safe flight,” she says. “Text me when you land.”

“I love you,” Potter says.

“And I love you,” Ava says. She walks Potter out to the main hallway and waves to him until he disappears around the corner.

It’s ten o’clock that night, and Ava is lying in bed listening to Schubert’s Impromptu no. 3 in G-flat Major on her headphones, her eyes searching out the window for what she imagines to be the contrails of Potter’s plane.

Ava’s phone rings.

Potter? she wonders. It’s too late for it to be anyone else. His flight was supposed to take off at 9:4

5. He texted to say he was boarding, then again to say he was powering down. Maybe they’re delayed, sitting in an endless line of jets waiting to head to Europe, and Potter is bored and he wants to hear Ava’s voice one last time.

But when she checks her phone, she sees it’s Margaret calling.

“Mom?” Ava says.

“Oh, honey,” Margaret says.

BART

When he and Allegra have been dating for six weeks and three days, Bart receives an e-mail from the Marine Corps, and suddenly, Bart realizes, he and Allegra have to have a conversation about the future.

He takes Allegra to dinner at the Greydon House, and they are seated at one of the tucked-away tables in the bar. The Greydon House is the new hot spot on Nantucket; Bart remembers when it was his dentist’s office. It has been reimagined as a hotel and fine restaurant. The bar is dark paneled, the lighting is low, the furniture is ornate, and the overall effect is one of an exclusive club. Allegra mentioned that she has always wanted to come here, and since Bart is now in the business of Allegra wish fulfillment, he has brought her here for dinner.

He orders a cocktail called the Grey Lady, which is served in a cod-shaped mug. Normally, he doesn’t drink around Allegra, but tonight he needs to share his news and he’s not sure how he’s going to handle it.

“I got an e-mail today,” Bart says. “I’ve been approved for officer training. I report to Camp Lejeune on January thirtieth.”

Allegra nods slowly. “Where is Camp Lejeune?”

“It’s in North Carolina,” Bart says.

Allegra stares at her salad. It’s baby greens with all kinds of treasures hiding—radishes, roasted beets, pumpkin seeds. Meanwhile, Bart got the lobster bisque, which the server poured out of a pewter pitcher tableside. The food here is artwork.

“So you’re leaving?” Allegra says. “You’re leaving Nantucket?”

Bart reaches for Allegra’s hand under the table. They have been so caught up in each other, so busy enjoying the present and learning about each other’s past, that the future hasn’t mattered. But Bart did tell Allegra he wanted to go to officer training school. He told her at the very beginning, that first night at his party. Right? It seems so long ago now; Bart can’t remember. Bart’s positive he told her. She probably heard him but didn’t think twice about it because she didn’t realize they would fall so deeply, desperately in love.

They’ve been together six weeks. Six weeks from now Bart is leaving for North Carolina.

“I want you to come with me,” he says.

“You do?” she says.

“I do. You can live with me on the base. You can get a job. You can take real estate classes. We can be together.”

Allegra hunts through her salad like she’s looking for the answer there. Bart is waiting for her to say she won’t go or can’t go or she doesn’t want to. She’s happy on Nantucket, she has a job, she’s comfortable. Bart will try to explain that being uncomfortable is what helps you to grow. Allegra needs to leave Nantucket and get out of her parents’ house—maybe even more than Bart does.

Bart is so sure that Allegra is the woman for him that he won’t be told otherwise. Over Thanksgiving, Patrick pulled him aside and told him to “be careful.” Patrick said that things between Bart and Allegra seemed to be moving “a little fast.”

Patrick said, “Dad can’t exactly give you advice, so I’m going to.”

Bart was even-keeled with Patrick instead of punching his lights out, which was what Bart wanted to do. Patrick had always been Bart’s favorite brother, and all the times when Patrick had acted as a surrogate father, Bart had been grateful. Paddy was younger than Kelley, and way cooler. But Bart is a grown man now. He has endured things Patrick can’t fathom. Bart isn’t going to have Paddy tell him how to live his life.

Patrick does have a good marriage. Bart will give him that.

Long ago Kelley told Bart way more than Bart wanted to know about Kelley’s own marriages. Kelley and Margaret had loved each other, but they had lived in a pressure cooker. “It was Manhattan in the nineties,” Kelley said by way of explanation, but Bart had no idea what that meant. Ultimately, the relationship had proven unsustainable. “That sometimes happens when you get married too young,” Kelley said.

Bart is sensible enough to realize that his relationship with Allegra might not pan out. Allegra might be miserable, unfulfilled; she might prefer one of Bart’s superiors—or subordinates—to Bart. He knows there are risks. But he also knows that some relationships between young people do weather the storm. It takes hard work, dedication—and good luck. Bart feels like he’s due some good luck; he has had enough bad luck to last a lifetime.

If Allegra refuses, will Bart leave anyway? Will he say good-bye to this girl, this new love, this person who is rapidly becoming Bart’s best friend on top of everything else?

No. He’ll stay. He won’t want to, but he will stay on Nantucket for Allegra.

Allegra smiles at him. “I feel like my parents will say it’s too soon. They’ll say we barely know each other…”

“It is soon, I realize that,” Bart says.

“But I don’t care!” Allegra says. “I’ll go with you wherever you want. North Carolina, Alaska, Germany, Mars.”

“You will?” Bart says.

“Yes,” Allegra says. “I will.”

Bart drops Allegra off that night, then sits outside her house on Lily Street until he sees the light go off in her bedroom. He is so happy he’s dizzy. Allegra will come with him. He doesn’t have to be alone ever again.

Bart floats up the side steps of the inn until he smells smoke and sees the glowing tip of his mother’s cigarette in the dark.

He can’t wait to tell Mitzi the news. It will make her so happy.

“Mom?” he says.

As he gets closer, he hears Mitzi crying. “We’re losing him,” she says.

MARGARET

This year Margaret is all about Christmastime.

She buys a tree from the Korean deli on the corner. It’s small, but it’s the first tree Margaret has owned since she and Kelley and the kids left the brownstone on East Eighty-Eighth Street.

Of course, one can’t buy only a tree, Margaret realizes, once her doorman helps her get it upstairs. She has to buy a stand. And lights. And ornaments. She goes to Duane Reade but keeps her sunglasses on in the store so as not to be recognized. It’s far worse being recognized now than it ever was when she was working. First of all, when she was working, she rarely ventured out on the street to do everyday errands like this. Second of all, the general population of New York seemed cognizant of the fact that Margaret Quinn was busy and therefore not to be interrupted for photos, political opinion sharing, or reminiscing. Now that Margaret is retired, she has become fair game. When people recognize her, they want to stop and tell her how much they loved her broadcasts, how much she meant to them, how the “new girl” has an annoying lisp. Then they start to talk about Trump, and this is when Margaret always excuses herself.

She gets a tree stand at Duane Reade as well as a box of four hundred white lights. She inspects the boxes of ornaments, but the offerings look sad and cheap. New York is the center of gross consumerism. Surely there must be a store—or many stores—dedicated solely to Christmas ornaments.

It’s Always Christmas in New York, on Mulberry Street down in Little Italy, Google tells her. And the Christmas Cottage, on Seventh Avenue.

The next day at the Christmas Cottage, Margaret fills her basket with ornaments. She and Kelley used to collect ornaments when they traveled, and they added those to the ornaments Kelley inherited from his mother, Frances, in Perrysburg and Margaret’s from her family. They topped the tree with the angel they had bought from the shop at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, commemorating the day they met. That’s how one is supposed to acquire ornaments, Margaret thinks: bit by bit, with each ornament telling a story.

But oh well! Whatever ornaments Margaret used to have went with Kelley to N

antucket. And she and Drake need ornaments, so Margaret continues to pick and choose the prettiest, most tasteful ornaments she can find. The story behind all of these ornaments will be the same: These are the ornaments I bought at Christmas Cottage on Seventh Avenue once I retired from CBS and rediscovered Christmas.

That very same afternoon Margaret decides that she is going to string popcorn and cranberries into a garland. She figures out how to do this using Martha Stewart’s website. Martha Stewart is a goddess, Margaret realizes. The breadth and depth of her empire takes one’s breath away.

The garland requires another trip to Duane Reade—for fishing line and a sewing kit—as well as a trip to Gristedes for the popcorn, cranberries, and vegetable oil. Nope, forget the popcorn and oil; Margaret buys two packages of Jiffy Pop instead. She has fond memories of watching the foil dome rise over Melanie Jerrod’s hot plate in the dorm at the University of Michigan.

By the time Drake gets home from the hospital that night, Margaret has made two pans of Jiffy Pop, which when combined with two bags of cranberries, yielded thirty feet of garland. She poked herself with the needle innumerable times, but the garland looks just as it is supposed to. Margaret has Johnny Mathis carols playing, and for supper she has made a pot of cheese fondue! Not only did she carefully melt the Gruyère, Emmenthaler, wine, and kirsch, she also cubed and toasted a baguette and sliced up summer sausage for dipping. The recipe for fondue was also on Martha’s website. It suggested drinking a crisp Riesling, as the dryness of the wine offsets the richness of the fondue.

“Look!” Margaret says as she hands Drake a chilled glass of Riesling. “I made garland. And I bought ornaments! We can decorate the tree, then eat.”

“I can’t believe this,” Drake says. “You were so productive today.”

“Wasn’t I?” Margaret says. It’s astonishing how much one can accomplish when one doesn’t have to work. And Margaret didn’t check the news all day, not even once.

What Happens in Paradise

What Happens in Paradise Reunion Beach

Reunion Beach The Sixth Wedding

The Sixth Wedding 28 Summers

28 Summers Summer of '79: A Summer of '69 Story

Summer of '79: A Summer of '69 Story Troubles in Paradise

Troubles in Paradise The Perfect Couple

The Perfect Couple Winter Solstice

Winter Solstice Barefoot: A Novel

Barefoot: A Novel